Article 4 in our series Executives’ Perspectives on Digital Transformation

by Thomas Gessner, Business Development Manager MBSE Solutions, Zuken.

In our previous articles of the series Yasuo Ueno and I delivered a clear warning: the era of document-based engineering is over. In today’s environment of exploding product complexity and relentless market pressure, no team – no matter how skilled – can keep pace using scattered files, manual coordination, and static documents. Decisions slow down. Risks accumulate. Innovation stalls. At its core, this is not an efficiency problem— – it is a complexity management challenge that traditional, document-based engineering can no longer solve.

The simple truth is that the traditional way of working cannot survive the scale and speed modern engineering demands. If manufacturers want to compete in a world defined by uncertainty and interdependence, they must move beyond documents and adopt a model-centric approach. Only then can they gain the clarity, speed, and confidence needed to thrive in Digital Transformation.

Why Complexity Management Might Be Our Competitive Advantage

When it comes to achieving product success today, the challenge can be summarized in two words: speed and complexity. In fact, these two elements are tightly linked. A perceived loss of speed is often the direct result of rising complexity. But this relationship is frequently misunderstood, and as a consequence, many organizations try to increase development speed without addressing the deeper structural issues.

To understand how to navigate this dynamic, it helps to look more closely at the four main dimensions of complexity:

- Product Complexity

- Portfolio Complexity

- Process Complexity

- Value Chain and Market Complexity

Product, portfolio and process complexity are internal drivers of complexity, whereas value chain and market complexity are elements of the VUCA environment (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity) in which companies operate. All four of these factors are, of course, intertwined and interdependent.

The increasing complexity of products can be clearly seen by looking at them. For a long time, products have been turning into complex mechatronic systems.

Increasing complexity can be observed in growing portfolios, which are often rather organically grown than actively managed, and in the processes from sales to engineering, in which products and customer-specific solutions are developed. Complexity drivers also exist in the distributed value chain and in the economic and regulatory environment in which any company operates.

The perceived loss of speed in responding to market opportunities is therefore not primarily an efficiency problem. It is a complexity management problem. Processes slow down because more effort is required to understand dependencies, resolve inconsistencies, and coordinate across multiple dimensions.

In this context, complexity management means the ability to understand, structure, and control interdependencies across products, portfolios, processes, and value chains—without sacrificing speed, quality, or flexibility.

This distinction matters. Attempts to increase speed – for example, to compete with fast-moving global competitors – without addressing underlying complexity are likely to produce negative side effects: reduced quality, higher risk, and organizational strain. Understanding speed as a function of complexity shifts the focus away from pure productivity measures toward a more fundamental question: How do we manage complexity effectively?

Is Complexity Really the Enemy?

One possible response would be to simplify products in order to increase speed and agility. But this is rarely a viable strategy. Product complexity is often the very source of differentiation and customer value.

Addressing the complexity issue means two things:

- Start with the product and the portfolio, as these elements are the main complexity drivers

- Develop a strategy to manage complexity in such a way that a potential loss of speed is more than compensated for by the added value and flexibility of the product.

In short: We should start to use complexity to our advantage. Solving the complexity challenge, however, is likely to have noticeable positive effects on process velocity. The question is: What could be an approach to accomplish this?

It might make sense to take a step back and ask: Is complexity really a bad thing? When it comes to product complexity, the answer might be no. At least not always. Why?

Complexity can be a key differentiator in multiple dimensions: Complexity often is the result of advanced product functionality; it can be the result of products that offer customer-specific functionality; it can be the result of products that can be adopted to different tasks and use cases; and it can be a consequence of making products more sustainable and environmentally friendly.

As a first insight, we must obviously differentiate between “wanted” and “unwanted” complexity (in very much the same way as we differentiate between “desired” market variety and “undesired” internal product variety). How can this be accomplished?

From Copy-and-Paste to Model-Based Reuse

Here is an example: A manufacturer of large-scale industrial plants has 15 different product lines. Inside these product lines, each customer project appears to be a unique solution, specific to the customer, their functional requirements and the environment the plant will have to operate in. Consequently, the offer process takes months and, in some cases, even years and new projects are being created by copying previous projects.

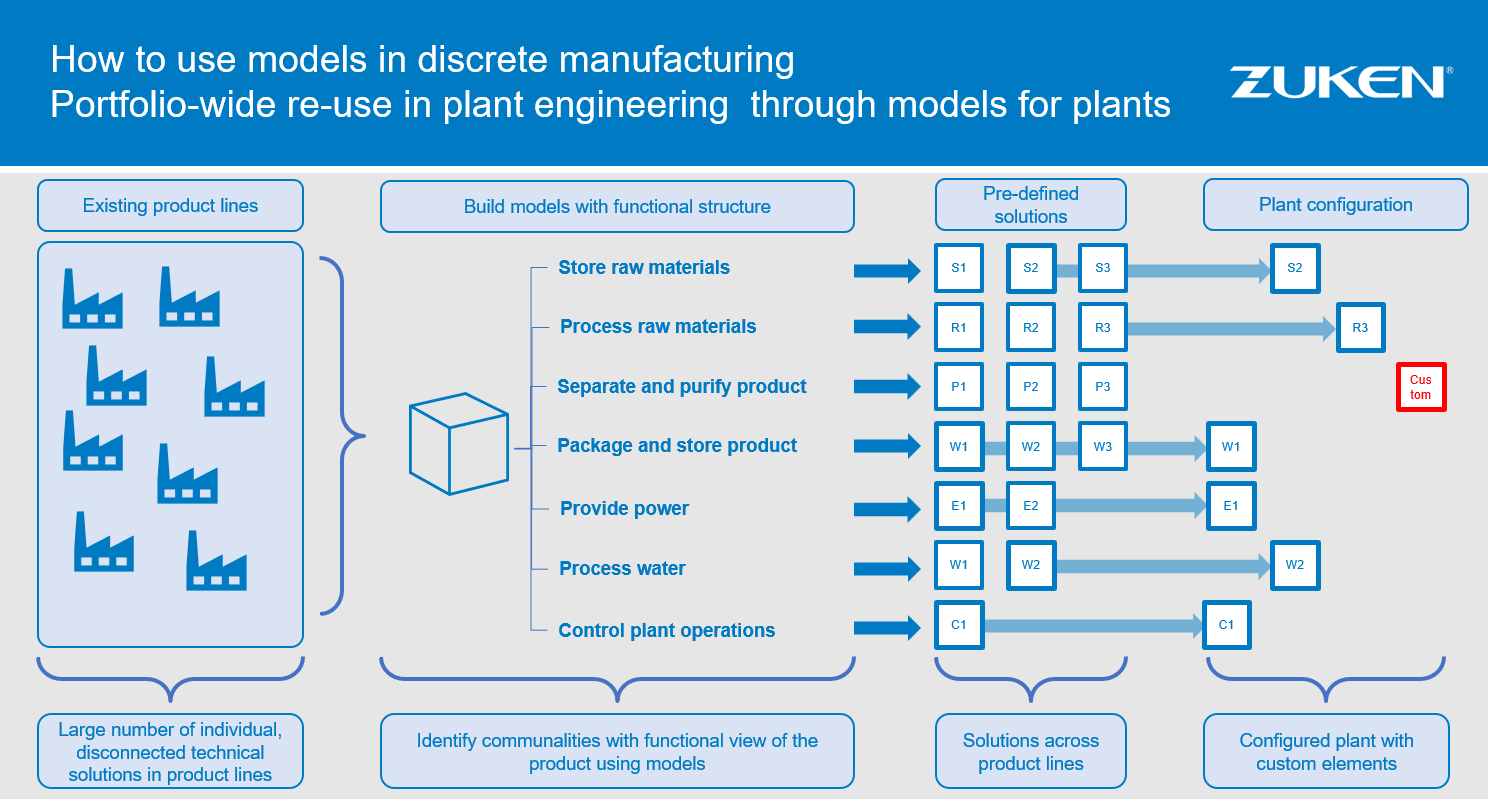

Therefore, not only is the proposal process slow and complex. Also, the product itself is a compromise, as unwanted or unnecessary features are being incorporated in the new project in the process of copying an existing plant. In this case, the plant manufacturer moved from a copy-and-paste approach towards systematic re-use through pre-configuration of plants. This was made possible by moving from a document- and BoM-based way of working towards a model-based approach: Looking at a plant from the functional perspective of the product, synergies and redundancies (i.e. individual and thus partially redundant technologies for each of the 15 product lines) could be easily identified and optimized. In this case, a model-based approach enabled the plant manufacturer to use the functional structure of the model to identify and optimize communalities and speed up the proposal and order clearing processes significantly at the same time.

Using models to create configurable industrial plants: Communalities between product lines can be understood with a functional structure (middle)

Why MBSE Fits Beyond Aerospace

It is remarkable that MBSE and a model-based approach seems to prove applicable in areas such as industrial machinery and plant engineering with their business models catering for customer-specific solutions. At first sight this might seem a far stretch from the original applications of MBSE in aerospace engineering. But it makes sense: MBSE was always conceived as a systematic approach to complexity management, enabling organizations to control interdependencies across engineering domains and the value chain. Add the dimension of disciplines of the value chain to this and you have both the required “vertical” engineering alignment and the “horizontal” value chain alignment in one approach (visualization).

Ultimately, complexity is not the enemy – poor complexity management is. As products, portfolios, and value chains continue to grow in scale and interdependence, manufacturers need a disciplined, model-based approach to manage complexity without losing speed or control. MBSE provides the foundation for turning complexity management into a sustainable competitive advantage.

We might want to examine further how the business models in discrete manufacturing can be addressed with a model-based approach. Specifically: Configure-to-Order and Engineer-to-Order products and processes. MBSE might be at the core of a strategy to use complexity to our advantage. One of the key questions will be: How can this approach be made to work for industrial and discrete manufacturing use cases?

Also in this series

- Blog

Executives’ Perspectives on Digital Transformation #3

- Blog

Executives’ Perspectives on Digital Transformation #2 The Productivity Paradox

- Blog

Executives’ Perspectives on Digital Transformation #1 Building Dynamic Capabilities for Product Success in a Changing World